The global energy transformation will affect social, economic and environmental factors that are often among the root causes of geopolitical instability and conflict. Climate change, rapid urbanization, high unemployment, discrimination, inequality and other major trends can create conditions that increase poverty and exclusion, promote the mass movement of people, cause violent conflict, and political extremism—all forces that have the potential to affect geopolitical stability. While the characteristics and rapid growth of renewables will generate new risks, the energy transformation will also create opportunities to overcome some of these challenges.

Economic and social tensions

The energy transition involves a profound economic, industrial and societal transformation. It could affect prosperity, employment, and social organization as much as the first Industrial Revolution. The shift to renewables brings several macroeconomic advantages. For example, by 2050, the cost of energy could fall from 5% of global GDP to a little over 2% of a much larger world economy.132 However, it may also create new social divisions and financial risks that could reverberate through the international system and be geopolitically significant.

Mitigating social dislocation

While the switch to renewable energy has the potential to create an additional eleven million jobs in the energy sector by 2050,133 it may at the same time reduce employment in specific sectors such as coal mining. The most labour-intensive form of fossil fuel extraction, the coal sector employs a global workforce of at least 9 million people, more than half of whom are employed in China.134 Coal mining jobs are threatened by structural market forces including cheaper alternatives and automation, and by government regulation to protect human health and the environment.

In China, the world’s largest coal producer, coal mining accounted for around 5 million jobs in 2016, out of a work force of some 800 million.135 However, coal jobs are concentrated in particular regions and labour is the least mobile factor of production. Mine closures frequently have a deep and long-term impact on local communities and economies, causing marginalization, social dislocation, and disputes between workers and employers.

The energy transformation may deepen existing political divisions or create new ones that in their turn create geopolitical consequences. Coal miners were among the most vocal supporters of Donald J. Trump during the 2016 US Presidential elections; and recent cabinet changes in Australia and France can be linked directly to disagreements over the energy transition.136 In 2013, the Bulgarian government resigned amid a wave of violent protests over rising electricity prices, partly due to an overgenerous feed-in-tariff to renewables. In China, protests against air pollution have spurred the government to make the fight against it a political priority.137 In many of the countries in which governments have attempted to phase out fossil fuel consumption subsidies, protesters have frequently taken to the streets to oppose such reforms.138 More than a quarter of a million French people protested in late 2018 against a rise in fuel prices tied to a new carbon tax.

There is some evidence that, while difficult to put into practice, policies that facilitate a ‘just transition’ can help to address the serious socio-economic difficulties faced by coalminers and their families and other communities of work whose skills are made redundant by new technologies.139 Measures that have been developed include the establishment of national or regional transition bodies, transition funds, on-the-job retraining programmes, infrastructure investments, and programmes to develop skills, education, and assist with relocation.140Spain recently provided an example of what can be achieved with enlightened leadership and progressive policies. The government came to an agreement with trade unions to shut down all coal mines by the end of 2018, while investing 250 million Euros in affected mining regions over the next decade.

Stranded assets

The global fossil fuel system has a built asset value estimated at 25 trillion US dollars141 and continues to add one trillion dollars of assets each year.142 A giant network of oil wells, coal fields, power stations, pipelines, oil tankers and refineries extends across the world. Yet no more than a quarter of total coal, oil, and gas reserves can be burned before the ‘well below 2oC’ target of the Paris Agreement is exceeded.143

Parts of the fossil fuel system could become ‘stranded assets’ as a result of policy action and the falling costs of renewable technologies. Asset stranding occurs when assets have suffered unanticipated or premature write-downs, devaluations or conversion to liabilities.144IRENA has noted that electricity generated from renewables will become cheaper than electricity generated by new fossil fuel assets in all major locations by 2020.145 It is therefore only a matter of time in many parts of the world before green electricity becomes cheaper than electricity generated from existing assets, at which point it would make sense to close down fossil fuel generators.

The process has already started. Since 2010, Europe’s electricity sector has already suffered impairments valued at more than 150 billion US dollars from write-downs of its thermal generating capacity.146 In the last five years, Engie has written off 35 billion Euros in fossil fuel assets.147

The risk of stranded assets might not be fully reflected in the value of companies that extract, process or distribute fossil fuels. Moreover, these assets are counted when countries calculate their national resources. Were the risks to be priced in, the value of these companies, and the credit ratings of certain countries, could experience a sudden drop. This might have systemic consequences, even trigger a climate ‘Minsky moment’,148 given the large sums involved. One study found that no less than 12 trillion US dollars of financial value could be lost in the form of stranded assets.149 To provide context, the Great Recession of 2008 was sparked by losses in the US subprime mortgage market of 0.25 trillion US dollars.

International bodies, such as the Financial Stability Board, are strongly encouraging firms to increase their disclosure of risks relating to climate change.150 By September 2018, institutions with over 100 trillion US dollars of assets under management had declared their support for the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

Climate, water and food security

Renewables will also induce geopolitical effects by mitigating climate change. Climate change will have widespread effects that defence and security experts call ‘threat multipliers’ because they can worsen scarcity of food and water, increase poverty, and aggravate risks of conflict and political instability. The UN Security Council has examined the impact of climate change on international peace and security since 2007.

Climate change can threaten the stability of countries in a number of ways. It causes rainfall variability, droughts, floods, hurricanes and fires. Rising food prices and water shortages can result in political and social unrest. Sea level rise is already threatening the survival and existence of many Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The destabilizing impacts of climate change can also lead to increased displacement and migration as people move to avoid extreme weather events or find water, food, land, jobs and a more secure life. These outcomes are already being felt in many countries, irrespective of their level of economic development or geopolitical standing.

Accelerating climate change will increasingly exacerbate geopolitical competition for water and food. Rapid economic and population growth are already increasing demand for those resources, especially in developing countries. By 2050, the demand for water and food is expected to rise by over 50%.151 The interplay between water, energy and food supply systems—the nexus—creates major geopolitical challenges for countries at a time of accelerating climate change.

Hydropower is the world’s largest source of renewable electricity and has its own geopolitical dynamics, particularly when transboundary rivers and water resources are involved. These dynamics are increasingly impacted by climate change. The damming of major rivers, for example, will increase the energy security of upstream states that benefit, but could harm water supplies, agricultural productivity and fish stocks in states downstream, which may already be experiencing rising water stress. Planned dams along the Nile, Mekong, Tigris and Himalayan river systems could all have major impacts on water availability downstream and create tensions among riparian states as a result. There are also examples of hydropower benefits. The Itaipu dam enables Brazil and Paraguay to trade electricity and share water, so enhancing sub-regional cooperation and stability.

Renewable forms of energy can help to reduce water stress. Renewables require water withdrawals 200 times lower than conventional energy.152 One study has found that, by 2030, if they combine renewables with improved plant cooling technologies, Chinese power generation could reduce water intensity by as much as 42% and emissions intensity by up to 37%.153 Renewable energy technologies also offer increasingly attractive solutions to power desalination, a vital issue for many countries in arid regions, including the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Vulnerabilities in water and energy supply also pose critical risks for food security, since severe droughts and fluctuations in energy prices can affect the availability, affordability, accessibility, storage, and use of food over time. Integrating renewables in agriculture (through solar pumps for irrigation or geothermal energy for food drying) can improve agricultural yields, reduce post-harvest loss, and ultimately enhance food security.

Any significant increase in competition for food, water, land, clean air, and other resources essential for life can create social and economic tensions that could in turn have geopolitical consequences. These can increase tensions between states but may also foster new forms of cooperation to tackle these challenges collectively.

A new development path

Social and economic tensions in a country can worsen if growth is not inclusive, services are captured by elites, or industrialization generates imbalances between regions. To achieve stability and prosperity over time, a country’s development needs to be inclusive and sustainable. In this sense, peace and development are two sides of the same coin. Both require policies and institutions to address environmental risks, reduce inequalities and ensure equity and social cohesion.

Energy lies at the heart of human development. It is a critical factor in economic activity and essential for the provision of human needs, including adequate food, shelter and healthcare. Energy also fuels productive activities in the wider economy, including agriculture, industry and commerce. In the last twenty years, millions of people have gained access to electricity. Developing countries in Asia, led by China and India, have made significant progress. Yet to achieve universal energy access by 2030, as agreed in the SDGs, these efforts will need to accelerate. On current trends, about 674 million people, mainly in Africa, could still be without power in 2030.154

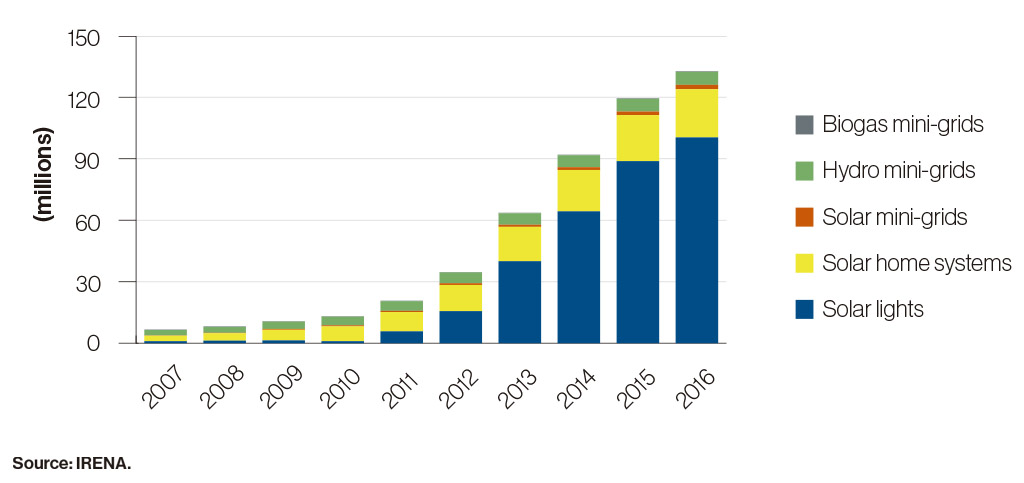

Historically, national electrification programmes have relied on large-scale, centralized power stations and line extensions powered by fossil fuels. Since around 2011, however, renewable energy has become an increasingly realistic alternative due to the confluence of two major trends: falling costs and mobile banking. A quiet energy revolution is now underway, providing light and power to households and entrepreneurs via off-grid renewable energy systems (see Figure 12). Estimates suggest that off-grid solutions (standalone and mini-grids) could supply approximately 60% of the additional generation needed to achieve the goal of universal energy access by 2030.155

Figure 12. Population served by off-grid renewable energy solutions

Improving access to energy brings numerous benefits that are vital for human development and therefore helps to create the conditions necessary for geopolitical stability. Energy poverty is typically considered a development concern because, for both individuals and communities, it reduces the quality of life and opportunities. However, it also compromises security. It poses a direct threat to the many women and children who are daily at risk of injury and violence when they gather fuel. More broadly, it is a threat multiplier,156 because it causes or exacerbates a wide range of problems, including poverty, marginalization, social unrest, population displacement, and environmental fragility.

Renewables also offer developing economies an opportunity to leapfrog, not only fossil fuels, but, to some extent, the need for a centralized electricity grid. Countries in Africa and South Asia have a golden opportunity to avoid expensive fixed investments in fossil fuels and centralized grids by adopting mini-grids and decentralized solar and wind energy deployed off-grid—just as they jumped straight to mobile phones and obviated the need to lay expensive copper-wired telephone networks.

Most importantly, renewables improve human welfare in ways that are not captured by GDP statistics. Properly designed, they can be applied to promote social justice and human welfare, encourage local empowerment and local wealth generation, contribute to a safer climate, improve public health, and advance gender equality and educational opportunities. The adoption of renewable energy will ease progress towards all 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals, not just the goal that relates to universal, affordable and clean energy.157